A neat solution for hydrodynamic heat transport

By Nicola Nosengo/NCCR MARVEL

When we think about heat travelling through a material, we typically picture diffusive transport, a process that transfers heat from high-temperature to low-temperature as particles and molecules bump into each other, losing kinetic energy in the process. But in some materials heat can travel in a different way, flowing like water in a pipeline that – at least in principle – can be forced to move in a direction of choice. This second regime is called hydrodynamic heat transport.

Heat conduction is mediated by movement of phonons, which are collective excitations of atoms in solids, and when phonons spread in a material without losing their momentum in the process you have phonon hydrodynamics. The phenomenon has been studied theoretically and experimentally for decades, but is becoming more interesting than ever to experimentalists because it features prominently in materials like graphene, and could be exploited to guide heat flow in electronics and energy storage devices.

In a new article in Physical Review Letters, MARVEL scientists from the THEOS lab at EPFL have made a leap forward in modelling and explaining phonon hydrodynamics. Their brand new mathematical description makes the phenomenon easier to test experimentally and clarifies the physics behind it. It also points to a bizarre phenomenon that can emerge with hydrodynamic transport and by which heat can flow in reverse, from a colder region towards a hotter one.

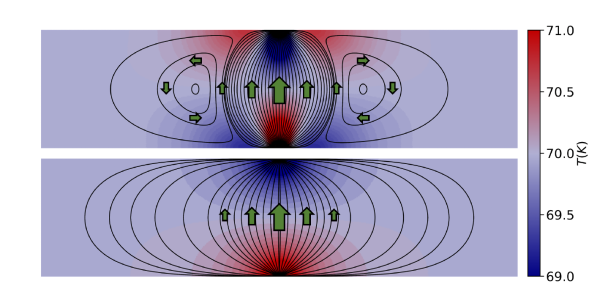

Temperature map in the 2D graphite strip, with streamlines shown for viscous (top) and diffusive (bottom) flow. In the viscous regime, negative thermal response arises from vortex-induced backflow opposing the main current, leading to negative thermal resistance across the strip. From https://doi.org/10.1103/g9dx-hjyn.

By re-expressing the VHE equations into two modified biharmonic equations (a type of partial differential equation that is often used for studying flows), the team obtained a fully analytical solution and used it to show that, in the hydrodynamic regime, the temperature emerges from two distinct contributions: one associated with the thermal compressibility of the flow and the other with its thermal vorticity. “This is an information you could not access with a numeric method” says Di Lucente. The thermal compressibility, which is formally described in this study for the first time, measures how much the phonon energy density varies in response to temperature gradients, while the thermal vorticity expresses the fluid’s spinning motion around a given point.

When applied to the in-plane section of graphite at a temperature of 70 K – that is much below standard room temperature – the equations show that a small but very surprising effect should arise. “By injecting heat at specific points, in addition to the normal heat diffusion in the center, you create vortices on the sides that push back heat from cold regions towards hot ones, a process we call thermal backflow. Thermal resistance across the device, in other words, becomes negative”.

Being able to insert such a system into consumer electronics products would have huge applications, for example hydrodynamic heat management could help prevent batteries or other devices from overheating.

“We are talking about only a couple Kelvin degrees, a very small effect” says Di Lucente. “But the equations don’t lie, the effect is there. It is up to us and to experimentalists to stabilize it enough to make it technologically appealing”. That would probably mean using a different material with a higher hydrodynamic temperature, and the very functions developed for this new study can guide towards the ideal conditions. “What we see is that the less compressible the fluid is, the more backflow you have”.

The fact that compressibility and vorticity are the fundamental variables at play also points to potential extensions of this method. “While in phonon hydrodynamics the flow is always compressible, electronic fluids are normally described as incompressible” says Di Lucente. “But there are special conditions where electron flows can be compressible too, like in plasmonics, and they are not well described by electron transport equations. Our method is a generalized description of flow that can be applied to phonons, electrons, and even magnons, that are collective magnetic excitations of particles”.

Reference

Di Lucente E., Libbi F., Marzari N., Vortices and Backflow in Hydrodynamic Heat Transport, Phys. Rev. Lett. 136, 056307 (2026), doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/g9dx-hjyn

Low-volume newsletters, targeted to the scientific and industrial communities.

Subscribe to our newsletter